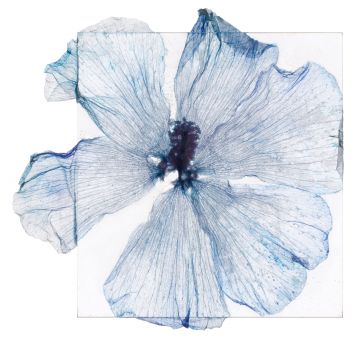

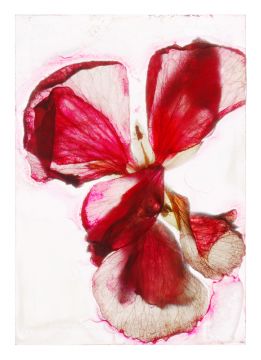

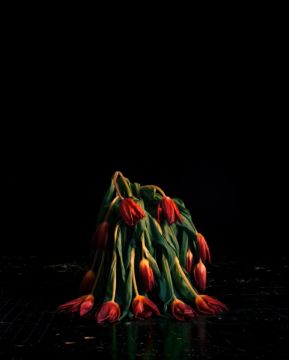

An Apparition Of Memory

Under a mantle of lime and salt crystals, the flowers seem to be preserved for eternity. For a brief moment we believe we can stop time and preserve the beauty and fragility of life.

My process-oriented work reflects the fragility of the ecological balance of our planet, questions our concept of transience, but also poetically shows the beauty and tenderness of withering and decay.

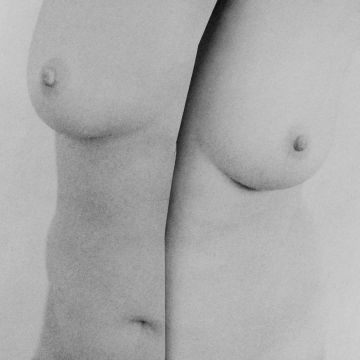

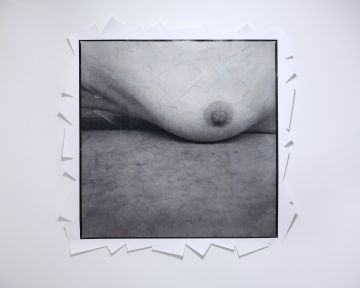

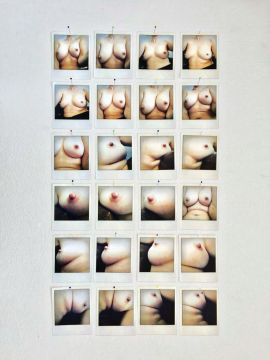

A Gaze of One's Own

While many of her past series contain elements from her personal life, 'A Gaze of One’s Own', titled in reference to Virginia Woolf’s essay 'A Room of One’s Own', is her first project explicitly grounded in her own experience and in which she is, as an artist, turning her gaze on her own intimacy and body. This project takes on issues linked to the artistic and cultural representations of the female body and to the reclaiming of the gaze, against the background of her own aging and changing body.

Her work has always been informed by her extensive knowledge – or rather her remarkable assimilation – of the history of photography. While it is not possible to pinpoint a single seminal influence in her work, her images effortlessly give nods to works from Man Ray, Balthasar Burkhard, Edward Weston or Francesca Woodman, to name a few. 'A Gaze of One’s Own' is nonetheless resolutely contemporary in its approach. It retains a performative dimension that has been characteristic of significant feminist artistic practices from the 1970s onward and is equally connected to the performance of self-representation shaped by social media over the last decade, which expanded the realm of self-representation with countless tools – and the accompanying norms – to edit and reshape bodies and features.

Her project reflects on and echoes the intensity of one’s relation to one’s body in the 21st century, the need to look at it, and to craft an image of one’s own. It confronts and combines imperatives which are sometimes conflicting in this particular era: reclaiming the gaze while offering a form of self-representation. Almost over a century ago, Woolf’s argued for a literal and figurative space for female writers. At the beginning of the 21st century, Lustenberger engages in a similar process towards the emancipation of her own gaze. It is informed by, but liberated from, centuries of primarily male representations of the naked female body: ‘I photograph myself, because I cannot objectify myself.’

The transitoriness of the female body, and in particular of her own, is another central element of this work, which has brought an unexpected area of freedom. As art history has primarily been focusing on the depiction of young and conventionally beautiful bodies, the artist’s own middle-aged body is less burdened by the weight of thousands of pre-existing representations.

'A Gaze of One’s Own' thus addresses important issues tied to visibility, representation and the gaze, and it does so with a courageous vulnerability, both in terms of exposing one’s intimacy and personal relation with one’s body and in terms of adopting a performative and process-based project.

– Danaé Panchaud, Director/Curator Photoforum Pasquart

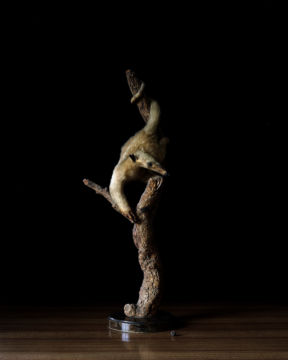

This sense of wonder

'I work on a multimedia installation called ‘This sense of wonder’. Designed as a great happening it will not only arouse the viewers’ curiosity but also their participation. [...] No camera can catch the ephemeral instant between life and death, but it can capture the time before and after it, the time of withering and decay. My installation gives the viewers an understanding of their own transiency and leads them into the wonders of deaths and its remains. Prints, projections, sculptures and many different lighting-and-view-devices elicit an uneasy pleasure that merges awe and dread, incredulity or even revulsion. We dive into a modern yet baroque universe. […] In my site-specific installation the viewer walks around slide projectors, light boxes, light desks, self- designed luminaries, slide viewing kits, and last but not least photographic prints. I focus on experimenting with the setting and staging of photographic images. My imagery reflects the media’s history and its function. Photography seems to snatch moments of time from mortality. But the captured moments are no more than representations of the past lingering on the beauty of decay. They are ephemeral like the electronic light that fuels the projectors: As soon as the power supply is cut off, the images fade into darkness without leaving a trace.' – Brigitte Lustenberger

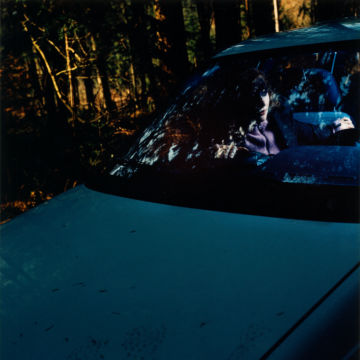

Watching

In Brigitte Lustenberger's 'Watching' series a dark, square-shaped image gives way to a view of a woman. Her heightened alertness expressed by subtle gesture, caused by something we don’t see generating an atmosphere of suspense, creating an image of something we might have seen before. The women are caught in a moment of raised awareness. Something unfamiliar seems to be going on. The photographs depict the moment just before the women realize what is happening – the moment of highest tension. Lustenberger stages situations which female viewers may recognize as if they have experienced them themselves, though in many cases their experience is limited to the virtual reality of movies and TV. The gaze in her photographs is an important tool to create a narrative and to question the viewer’s notion of looking and watching.

Ort des Geschehens

What looks like a particular scene – maybe a crime scene – questions the viewer’s perception of watching and seeing. In Brigitte Lustenberger’s ‘Ort des Geschehens’ (‘Place of Events’) the images are a deceit, as there has no crime been committed, nothing has happened at all – even when the image suggests so. The viewer falls back on memories of film scenes in order to read the image. The main subject of this series is not what we see in a photograph but what we make out of it. The absence of content heightens the sense of a detached nothingness that becomes a trope with the medium and raises questions about what photography is or does. Every photograph has an individual subtitle suggesting a possible reading, alluding to each scene a fictional narrative.

I Am Watching You

Three young women in profile depicted in a style that references 17th century portrait paintings appear to be trying to catch somebody’s gaze. Without moving their heads, they try to detect who is gazing at them. They struggle to see yet not turning their heads; they hold the gaze yet avoiding being noticed. Brigitte Lustenberger’s ‘I Am Watching You’ refers to her other series ‘Watching’. The women in ‘I Am Watching You’ go one step further than the women in ‘Watching’ and address the voyeur/the viewer by holding the gaze at the camera. The title ‘I Am Watching You’ addresses both the implied voyeur in the image/the viewer of the image who looks at the women and the woman who is about to detect the implied voyeur/the viewer. By gazing at the viewer, the women challenge the viewer and force him or her to reflect on his or her own activity of looking: What or who am I looking at – and who is looking at me?

Sights

Brigitte Lustenberger’s ‘Sights’ series is about places where something might have happened. The photographs are like film stills – the before and the after is missing. The absence in the photograph causes the viewer to construct a narrative about what might have been before the image was taken. The subtitles are fictional names, birth and death dates which are suggesting a possible reading, alluding to each scene a fictional narrative.

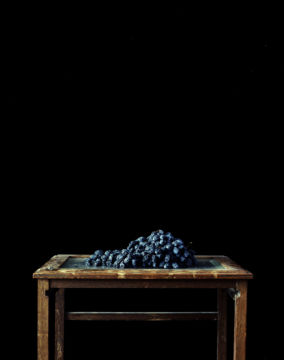

Still Untitled

Still lifes metaphorically show the transitoriness and the man-made interventions and changes of fate. Brigitte Lustenberger has been dealing with the theme of transience for some time now - on several levels. On the one hand, there is the selection, the staging, the observation of the 'passing and withering' of objects and the photographing, the capturing on negative, which is equivalent to the pausing of a moment. Thus Lustenberger reflects on life and death, our transience - and works against it by trying to counteract decay (in a photographic way).

On the other hand, she intensively explores the medium of photography. Photography seems to stop transience, because it captures moments and seems to snatch them away from transience. But these captured moments are ultimately only representations of the past - a (supposed) imprint of an object or an event. It is therefore easy to understand that all her photographs are created in an analogous manner (negative and photographic print). The light leaves an 'imprint' on the negative, which is then left on photographic paper by a light source. In digital photography, the light still draws on the digital chip, but as soon as the image is further processed, it is translated into binary codes and the visible trace of the light disappears in zeros and ones.

She works primarily with existing light, i.e. she worked only with window light. The exposure times are often very long, between a quarter of a second and several minutes. This results in a fine light that brings the subjects out of the dark: the light draws and paints - a homage to analogue photography. The process of leaving traces on the negative thus becomes an intense experience in itself.

Windows

The night is dark. Only a few windows illuminate the blackness of the night. What stories, what people are hidden behind the glass? We can watch but only guess and never know. A short subtitle and the uncanny point of view of the camera imply some story. The coarse grain of the photographs evokes a more two-dimensional, almost painterly effect. The viewer can’t be sure if the houses are real or film props. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window was a great inspiration for this project - playing with the human curiosity of what might be hidden behind the windows and their curtains.