Erotos

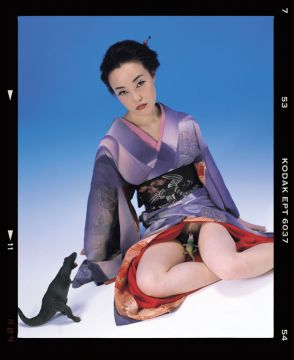

Love-Dream, Love-Nothing

69YK

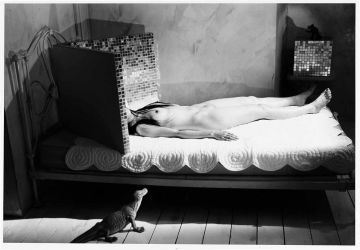

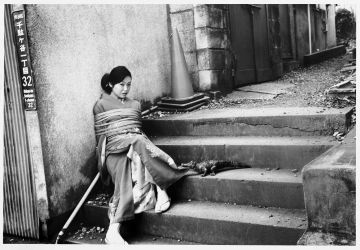

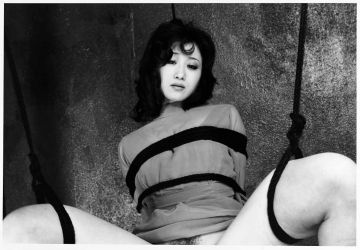

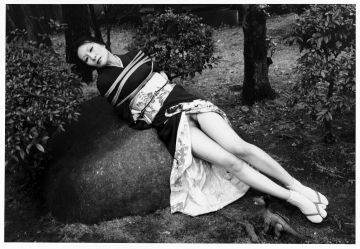

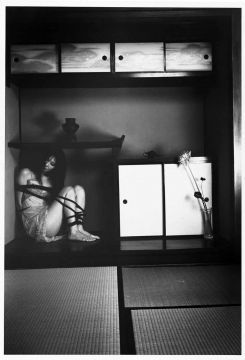

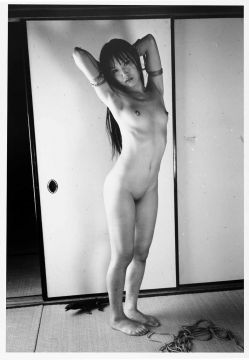

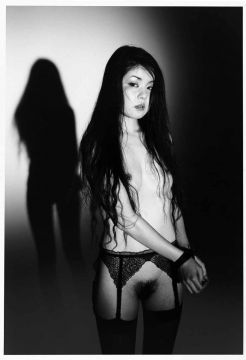

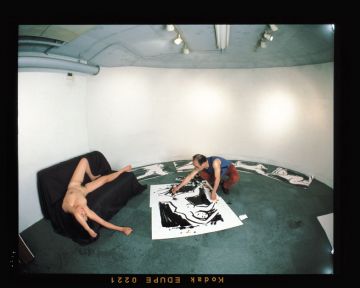

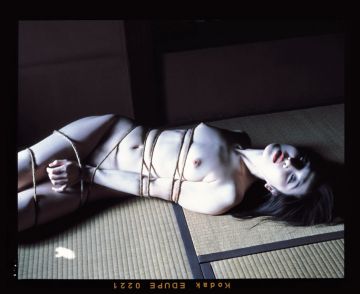

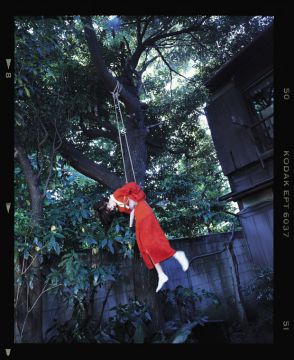

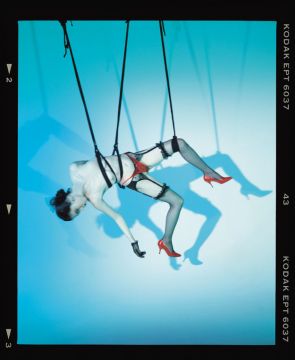

Araki, who continues making Eros (sex/life) and Thanatos (death) the subject of his work asserts that photography is concerned with the “nature of relation and closeness”. He states that the relationship between himself and the subject is very important, but that the interference of the consciousness of another person is unnecessary.

By daring to use monochrome film, he devotes himself to strengthen his own faith with regards to photography. It seems that this attitude includes a sense of self-discipline. When looking at the works, in which Araki’s belief is crystallized, one can feel the affection of Araki towards his subjects – women, flowers, the sky – and the love that he receives in return; The works have a scent of an intense exchange of sentiment between the photographer and his subjects.

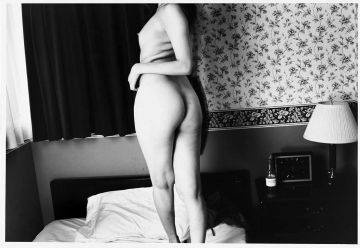

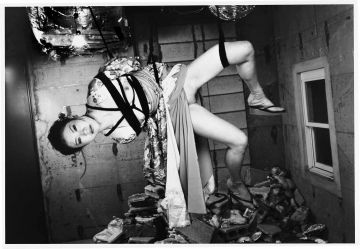

67 Shooting Back

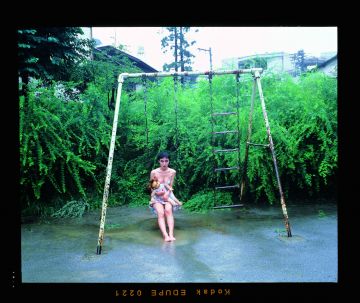

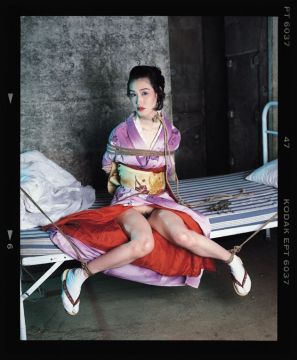

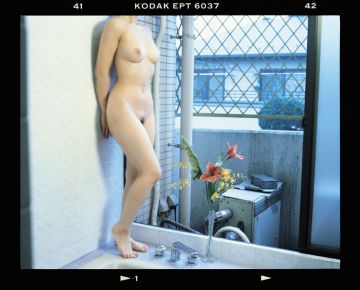

67 Shooting Back is a counterattack launched by Araki at 67 years old against digital photography and the status quo of beauty. Produced with a 6 x 7 film camera, this series gives prominence to married middle-aged women, who are identified by Araki as 'real women' of 'lives full of faults and with a dirty side.

When Araki says "All women are beautiful," it is not a metaphor. In fact, he took many photographs of the aura of dying flowers and married middle-aged women. Araki's emotions towards the subject lie etched in all of these photographs. However, he does not just stay in love with the subject. As he says, "I took many censorable photographs that I cannot include in publications. But I think the crazier, the better." He expresses his rebellious spirit as an artist.

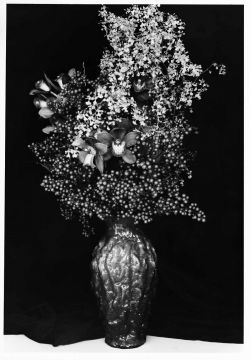

Flower Rondeau

Flowers preyed on Araki’s imagination as symbols of Eros and Thanatos since his childhood. Growing up nearby Jyokanji temple in downtown Tokyo, a place where spirits of courtesans from Yoshiwara were enshrined, Araki used to watch the cut flowers offered at the graveyards. To Araki, arranging decayed flowers is a form of revival, and photography records the beauty of brevity eternally.

Nobuyoshi Araki once observed that “to make what is dynamic static is a kind of death. The camera itself, the photograph itself, calls up death. Also, I think about death when I photograph, which comes out in the print.” In Flower Rondeau, one immediately notices the contrast between life and death, animated by a half-closed flower exposed against a dark blue backdrop. The veins of the flower emphasize its vitality, while its closed and withering petals demonstrates its fragility—and the fragility of life itself.

Araki’s floral still lifes can be viewed alongside the photographer’s kinbaku portraits as erotic and sexual visions. The opening and transparent petals are captured in a state of revealing, comparable to the various degrees of undress that his female models are shown. Flower Rondeau makes clear that the flower is a reproductive organ by highlighting both the stamen and carpal. As much as flowers die and decay they are also wombs wherein new life begins and the future materializes.

Literature S. Jerome, Araki, Cologne, 2002, p. 110 (illustrated)